Progressive Iterations

The power of compound improvements

Why Learning Through Fast Iterations Matters More Than Time or Effort?

We often take pride in the number of hours we grind, the weekends we sacrifice, and the long nights we power through. But in the modern world of creativity, innovation, and knowledge work, productivity isn’t about how long you work—it’s about how fast you learn.

Consider two teams working on the same goal:

Team A spends six months building what they believe is the perfect product.

Team B releases a prototype in week two, gets user feedback, adjusts, and repeats the cycle every week.

By month six, Team B has gone through 24 iterations. They’ve learned what works and doesn’t and refined their product accordingly. Meanwhile, Team A may discover they built the wrong thing, too late.

This is why fast iteration trumps sustained but static effort in fast-moving fields like design, software, startups, and writing.

I am conducting a Kaizen experiment to see if an agile requirement study using a pyramid of contents can reduce the number of reworks (lean thinking) compared with the traditional specification writing process. The idea arose from the 10-80-10 delegation/assignment rules (versus the 90-10 rule), plus the Pyramid of Communications framework.

Traditional Waterfall Documentation: Draft, internal review, and release a full-length requirement specification document for the end users to review (version 1.0 is 100% complete), reworking it based on subsequent feedback and inputs.

Agile Pyramid Documentation: Use layers of fidelity, starting with a high-level concept. Based on the validation of the high-level structure, we are progressively working on the mid-level and low-level (higher fidelity) requirements. We are sending the draft specification (high-level) at 10%, not 100%.

Similar to the “10-80-10” versus “90-10” assignment, getting alignment at the high level (strategy, structure) can reduce reworks due to misalignment or misunderstanding at a later stage. “Ready—Fire—Aim” instead of “Ready—Aim—Fire.”

The Myth of Time-Based Productivity

Clocking more hours doesn’t guarantee better outcomes. Ask the startups that pivoted five times before finding product-market fit or the designers who scrapped five drafts before landing on a viral concept.

“Working hard is not the same as working smart. Progress comes not from effort alone, but from learning what works and what doesn’t.” – Cal Newport, author of Deep Work.Time is a poor measure of growth if you repeat the same untested assumptions or stay in your comfort zone. What truly accelerates progress is feedback—rapid, frequent, and actionable.

Fail-Fast Fail-Forward: When you iterate quickly, you reduce the cost of mistakes and multiply your learning. A small experiment that fails fast teaches you more than a big idea that stays in your head.

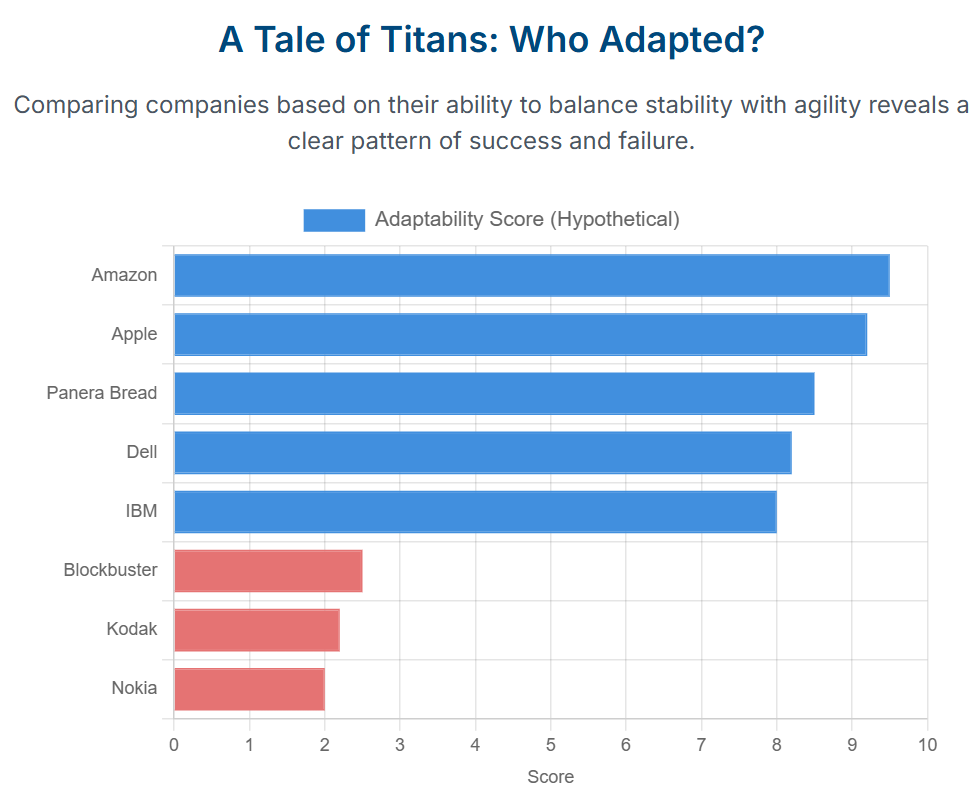

In business, we see the survival of the most adaptive, not the fittest.

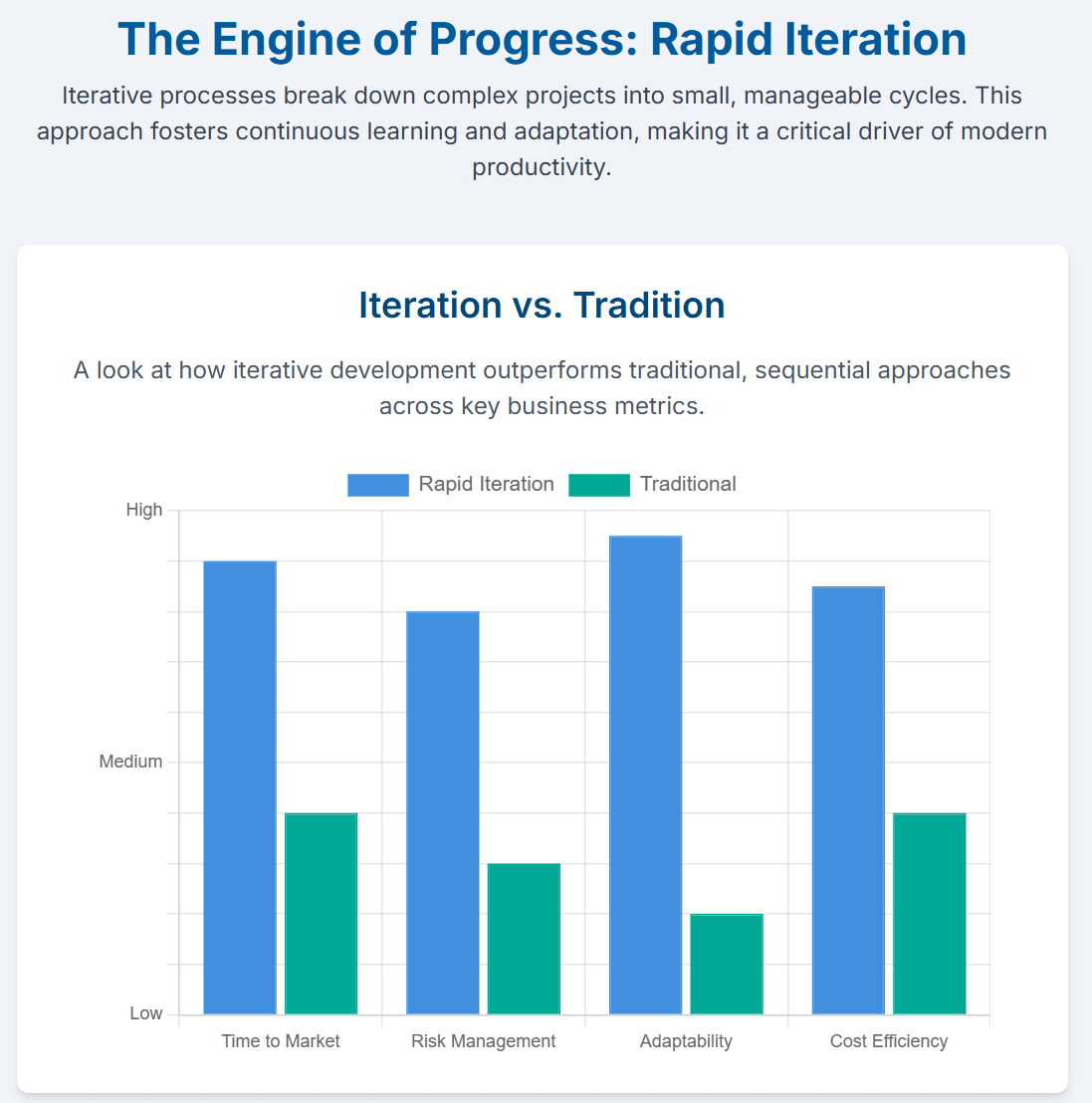

Rapid iteration has the advantages of faster time to market, improved risk management and adaptation to change, and greater cost-effectiveness in go-to-market productization.

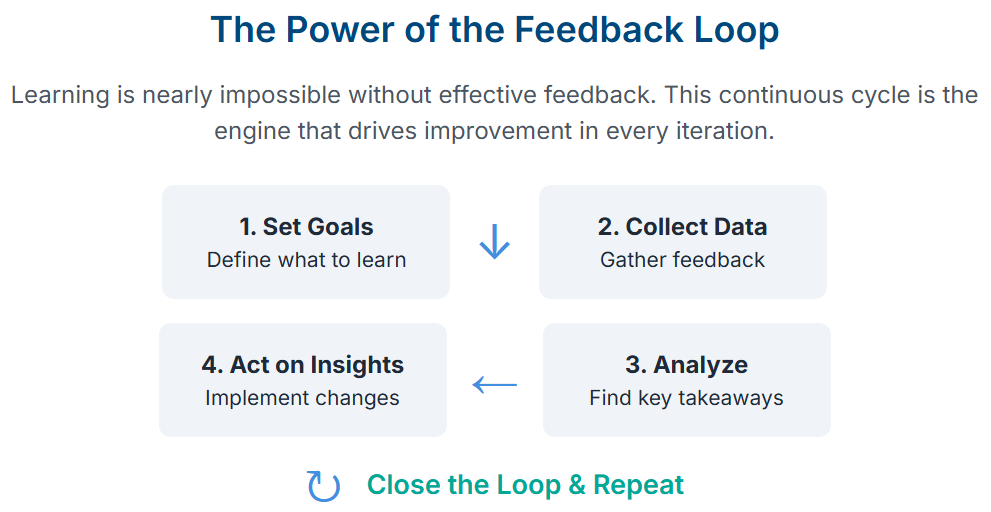

The Feedback Loop: A Productivity Superpower

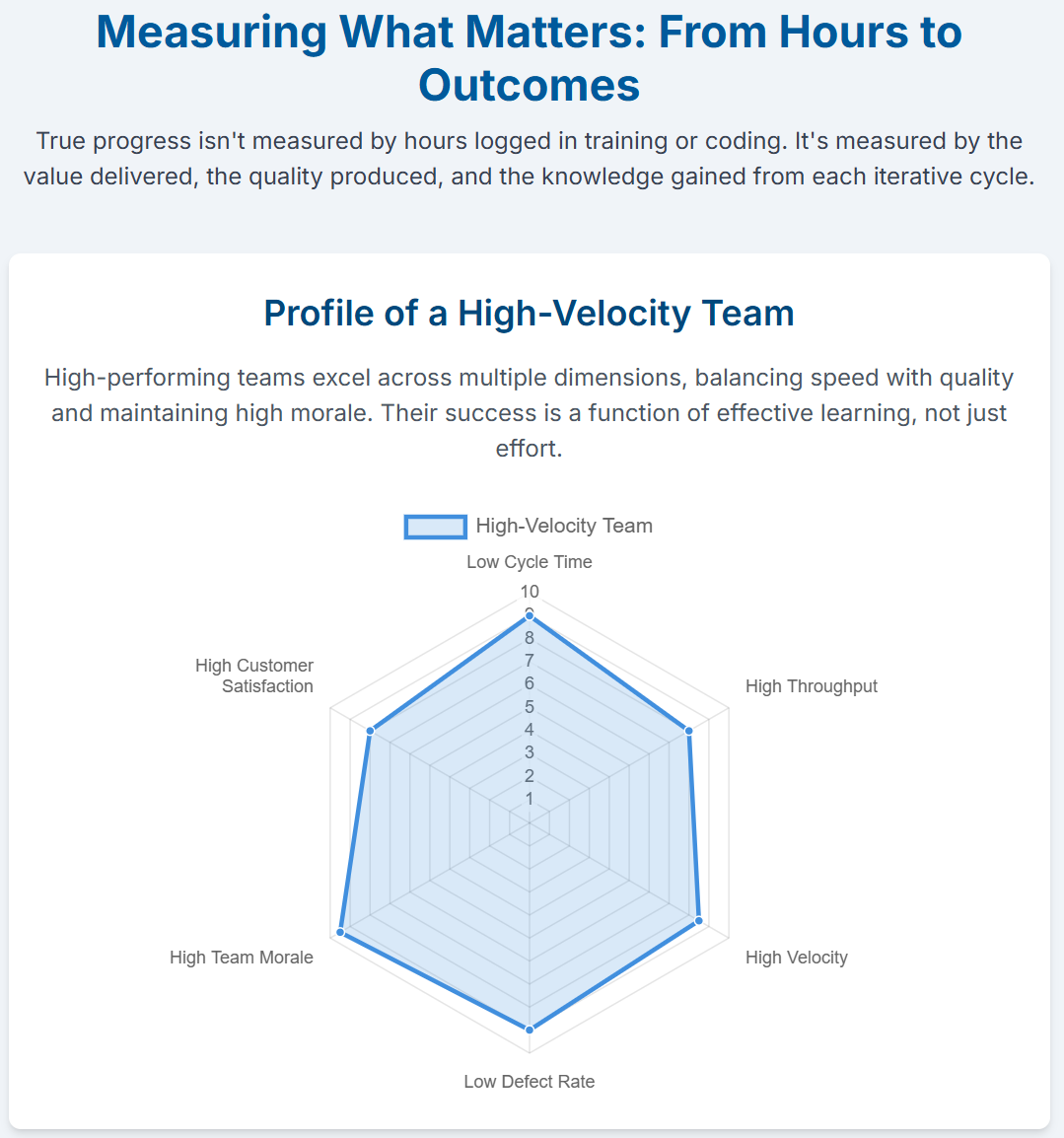

Think of productivity not as output per unit of time, but as insight gained per cycle. The more refining iterations we can carry out in a given duration, the higher the productivity.

Launch a version.

Observe what happens.

Learn from it.

Repeat—with improvements.

Learning from Evolution

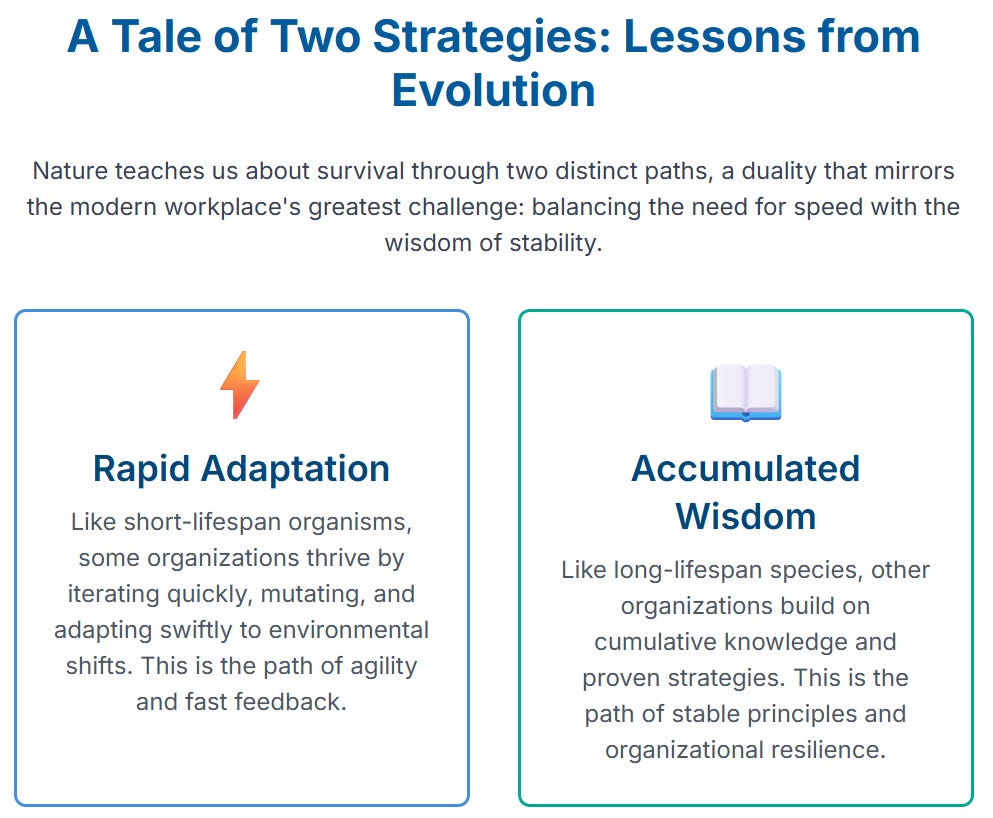

I notice that the evolution of species takes different strategies:

Some organisms, like bacteria and fruit flies, have short lifespans; hence, they could have more rapid genetic mutation. This is an idea for adaptation if the environment is changing rapidly.

Some organisms, like human beings and whales, have relatively longer lifespans and slow evolution cycle times. The parents take longer to pass the survival skills to the offspring. This is viable in a more stable environment, where knowledge and cultural inheritance give the group a long-term advantage.

This reflection highlights that ‘fast’ is not always good. For example, values and principles should be changed less frequently to maintain stability.

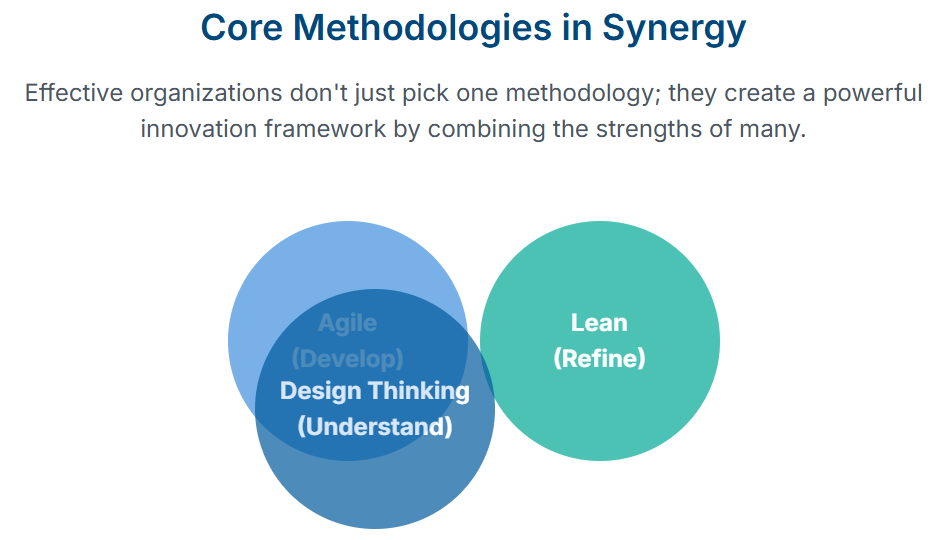

Hence, we have to use agile iteration (Kaizen), to reduce waste (lean thinking), and apply what we learn (knowledge) with design thinking.

Last week, I wrote about the lessons we can learn from F1 racing to build a high-performance team culture. I am impressed with Google Gemini Deep Research with Infographic output in less than 5 minutes.

Final Thought

Effort matters. But effort without adaptation is just spinning wheels. What counts is the speed and quality of your feedback loops—how fast you can observe, learn, and improve.

How to Embrace Fast Iteration:

Launch before you’re ready. Don’t wait for perfection. Fire-Aim

Seek feedback, not approval. Critique helps you grow.

Measure learning, not just outcomes. Ask: What did we learn this cycle?

Reflect and adjust quickly. Don't get stuck repeating old patterns.

So, next time we plan to spend N hours on a task, we can consider how many iterations we can do in M hours, where M is shorter than N hours.